THE RECONSTRUCTED KITCHEN AT MAGNOLIA MOUND

When Magnolia Mound was saved in the 1960s, the original detached kitchen no longer survived. In the early 19th century, kitchens were built separately from the main house to reduce the danger of fire, lessen summer heat indoors, and keep cooking odors away from formal living spaces.

Archaeology and Evidence

In 1977, archaeologists excavated the site of the kitchen, uncovering artifacts that reveal how food was prepared, served, and consumed:

-

Wine bottle fragments showed that wine and spirits accompanied daily meals.

-

Mocha ware, shell-edge English creamware, pearlware, and other ceramics reflected imported goods available through Louisiana’s river trade.

-

Flatware fragments, animal bones, and a nearby bone pit revealed a varied diet of wild game and domesticated animals—much smaller than modern breeds.

-

Crumbling bricks suggested the presence of a hearth or brick floor.

This evidence became the foundation for the kitchen’s reconstruction.

Rebuilding the Kitchen

With funding from the Junior League of Baton Rouge, work began in 1978 to recreate a kitchen appropriate to the 1830s. Builders used salvaged, historically appropriate materials and traditional methods to ensure authenticity.

Although a full brick floor was not confirmed archaeologically, the discovery of brick fragments inspired its use throughout the reproduction. Historically, only the area before the hearth would have been bricked, but soft handmade brick was chosen both as a nod to the evidence and as a practical choice for demonstrations.

To accommodate school groups, tours, and cooking programs, the reproduction was built slightly larger than the original. Construction was completed in 1979.

Interpreting Foodways

In 1980, the Junior League launched a program of open-hearth cooking demonstrations. Today, the reproduction kitchen highlights the skill of enslaved cooks, the specialized tools of their trade, and the labor-intensive nature of early 19th-century foodways.

Enslaved Cooks at Magnolia Mound

The kitchen was the heart of food preparation at Magnolia Mound, overseen by the plantation mistress but carried out by skilled enslaved cooks. Cooking required physical strength, technical knowledge, and constant attention to the fire.

Skilled Labor

Enslaved cooks were highly valued members of the household staff. They managed multiple fires, timed meals precisely, and mastered both French and Anglo-American food traditions. Records identify two male cooks purchased by owner Armand Duplantier: Raimond and Alcindor.

Daily Work

The workload followed the rhythm of plantation life. Preparing family meals was constant, but entertaining and feasts greatly increased the demands, often stretching cooks’ days from before dawn to late at night.

Meals for the enslaved community were separate. While no direct evidence survives that the main kitchen served both groups, enslaved workers typically received cornmeal and salted pork or bacon. They might prepare food in a separate kitchen, in their cabins, or—during harvest—receive meals in the fields to keep work moving.

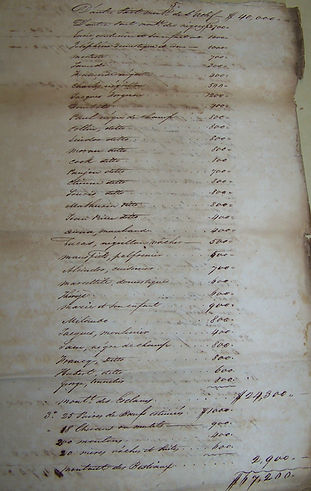

Armand’s bankruptcy, Louisiana Division / city / archives, First Judicial District Court – Case 57

Open-Hearth Cooking Techniques

Cooking at Magnolia Mound relied on open-hearth methods that demanded both skill and constant attention. In the kitchen fireplace, swinging cranes held heavy iron pots that could be moved closer or farther from the flames to control the heat. A sturdy lug pole with iron S-hooks suspended sausages and meats for roasting, while simple foods like potatoes and eggs were nestled directly into the hot ashes and coals. Cast-iron pots resting on the brick hearth provided steady heat for stews and slow cooking, and Dutch ovens—covered with glowing embers on their lids—served as portable ovens for baking breads, pies, and other dishes.

The brick bake oven was typically used once a week. It was preheated by burning a fire inside for two to three hours, then tested by sprinkling flour on the oven floor—if the flour browned quickly, the temperature was just right. Once the embers were cleared away, the oven retained heat long enough to bake breads, cakes, and pies.

Other tools and devices supported daily work. The olla jar, imported from Europe and originally used to store olives or oil, was buried partly in the ground and functioned as an early refrigerator. A glass cloche, bell-shaped and tinted aquamarine, sheltered tender seedlings in the garden like a miniature greenhouse.

Legacy

The reproduction kitchen is more than a reconstructed building. It invites visitors to explore:

-

Archaeology and reconstruction of a lost outbuilding.

-

Lives and labor of enslaved cooks, whose knowledge sustained household and community.

-

Tools and techniques that shaped early 19th-century foodways.

Together, these perspectives bring the kitchen to life as both a working space and a site of memory. It stands as a reminder of the skill, resilience, and creativity of the enslaved people who labored here—feeding both the planter family and the wider plantation community while living under the restrictions of enslavement.